Wittgenstein Miscellany

Influences on the early Wittgenstein

|

Gottlob Frege. The philosopher whose style Wittgenstein most admired. "I wish I could write like that," he once said. * |

|

Bertrand Russell; getting to know Wittgenstein changed his life. "We expect the next great advance in philosophy to come from Wittgenstein," he wrote. But Wittgenstein later said of Russell that he was "glib and superficial, though, as always, astonishingly quick." [Letter to G.E. Moore, 3.12.46], |

|

William James. Wittgenstein read his Varieties of Religious Experience -- emphasis on variety. He later thought of giving the following motto to his unfinished work, Philosophical Investigations: I will teach you differences. |

|

Leo Tolstoi. Wittgenstein read his Gospels in Brief while fighting in the trenches on the Eastern Front in World War I. "It virtually kept me alive," Wittgenstein wrote. |

|

Otto Weininger. Austria's second greatest crank. Wittgenstein read his Sex and Character, the thesis of which is that homosexuals are failed men and women are failed human beings. Wittgenstein said you could put a not-sign in front of it. |

|

Karl Kraus: "I cannot get myself to believe that half a man can utter a whole sentence." Wittgenstein's journals reflect his life-long doubt whether he could utter a whole sentence. |

|

Arthur Schopenhauer. Wittgenstein read his The World As Will and Representation "with relish" * at age 16; the Tractatus shows the influences of it. Later, Wittgenstein said he found Schopenhauer shallow. |

|

Gottfried Keller. Wittgenstein read his The Last Laugh in which a character says "I have no religion, except perhaps this: that when things go well for me, I tell myself they don't have to." Wittgenstein later said to his friend Drury that people in the modern age "must learn to live without the consolation of churches." |

|

Heinrich Hertz. German physicist and engineer, did seminal work on electromagnetism and light, proving they were two forms of the same fundamental energy. His theory that mathematical equations modelled physical reality influenced Wittgenstein's so-called picture-theory of language. |

|

Ludwig Boltzmann. Austrian physicist, did seminal work on atomic theory. Wittgenstein intended to study with him, but Boltzmann's untimely death in 1906 prevented it. |

Wittgenstein's work

|

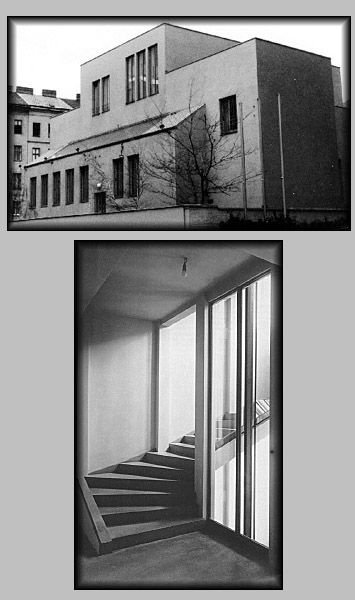

The house that Wittgenstein built, 1926-8, for his sister, Margarete Stonborough-Wittgenstein: Kundmanngasse, Vienna. He found architecture more intellectually challenging than philosophy. The outside looks like a bunker, but the inside is highly original. Wittgenstein designed everything down to the doorknobs and hinges. Like the Tractatus, it shows a lack of ornamentation, providing a 'logical space' for whatever contents the owner might wish to place there.

|

|

Wittgenstein carved a bust of his cousin in a style similar to that of Michael Drobil, whom he met in prison camp in Italy after WWI. |

|

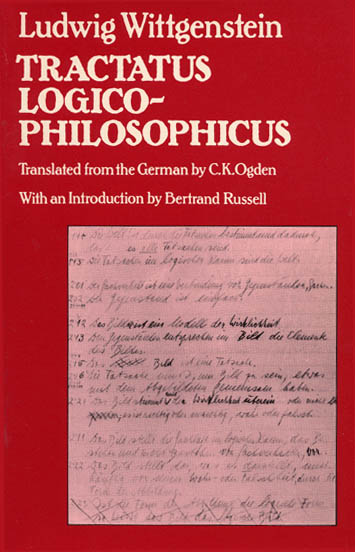

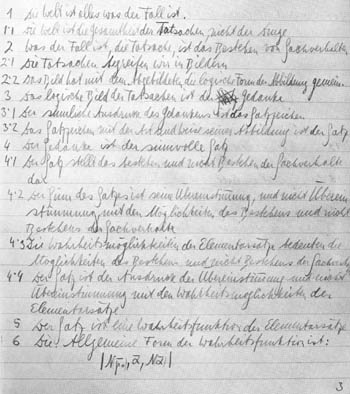

When Wittgenstein's work was first published in German in 1921, probably only three people in the world were capable of understanding it: Frege, Russell, and Frank Ramsey. Apparently, neither Russell nor Frege did, however. Ramsey met Wittgenstein, and he and Ogden translated the work. Correspondence survives attesting that the proofs of the translation were carefully revised by Wittgenstein. The translation appeared in English in 1922. The latin title was G.E. Moore's idea, based on its apparent similarity to Spinoza's Tractatus Theologico-Politicus. It is probably the shortest major work in the history of philosophy. The academic philosophical community generally received it with a mixture of awe and miscomprehension.

|

|

Wittgenstein's later work, published posthumously, consisted of dozens of scrapbooks containing numbered "remarks" which he cut and pasted together in different arrangements, again and again. His literary executors sorted, translated, and published them. The most significant, and most polished, is the Philosophical Investigations. In the Preface he wrote "I had occasion to re-read [the Tractatus] and to explain its ideas to someone. It suddenly seemed to me that I should publish these old thoughts and the new ones together: that the latter could be seen in the right light only by contrast with and against the background of my old way of thinking. For ... I have been forced to recognize grave mistakes in what I wrote in that first book." Much of the Investigations is a thorough, if not sytematic, attempt to expose not only the "grave mistakes" of the Tractatus, but also assumptions behind it. |

|

Translations. The Ogden/Ramsey translation of the Tractatus was corrected by Wittgenstein himself and renders the tone and feel of it very well. Later, Pears & McGuinness re-translated it, correcting a few grammatical mistakes. In several passages, they differed from Odgen/Ramsey 'simply to differ.' In translating the Investigations, Anscombe consulted native Viennese speakers cotemporary with Wittgenstein; she did not try to render the beauty of Wittgenstein's prose, but only its sense. She worked hardest on, and was more satisfied with, her translation of On Certainty. The translation she most respected was Roger White's (Philosophical Remarks). # |

|

Wittgenstein's rooms (formerly G.E. Moore's rooms) on the top floor in Trinity, Whewell's Ct. |

|

Ludwig's sister, Margarete Stonborough-Wittgenstein, posed for Gustav Klimt, 1905. The work was commissioned by her father, Karl Wittgenstein, as a wedding portrait. |

Wittgenstein on himself & others

"Am I the only one who cannot found a school, or can a philosopher never do this? I cannot found a school because I do not really want to be imitated. Not at any rate by those who publish articles in philosophical journals. ... I am by no means sure that I would prefer a continuation of my work by others, to a change in the way people live [sic--not 'think'] which would make all these questions superfluous. (For this reason I could never found a school.)" [Culture & Value, p. 61, 1947]

* These quotes from Wittgenstein were told to the author by Prof. Anscombe.

qFiasco on Wittgenstein:

|